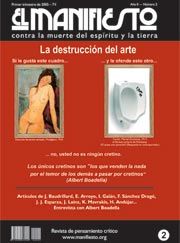

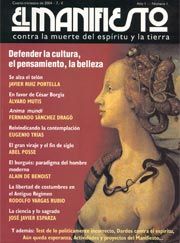

Texto del manifiesto

MANIFESTO AGAINST THE DEATH OF THE SPIRIT AND THE EARTH

Launched by Javier R. Portella with the backing of Álvaro Mutis

Those of us who have signed our names to this manifesto are not prompted to do so by any of the desires that usually motivate people to sign proclamations, protests and demands. The purpose of this manifesto is not to condemn government policies, denounce economic activities or protest against specific social activities. What we aim to challenge is something far more generalized, deep and therefore diffuse, namely, the profound loss of meaning that is undermining contemporary society.

It would be true to say that something similar to meaning still exists; something, which however surprising, still justifies and fills people’s lives today. For this reason, this manifesto aims, to be more precise, to speak out against the diminishing of this meaning to the function of preserving and improving (to a certain extent, it is true, unequalled by any other society) the material life of man.

Work, produce and consume; such is men and women’s perception of the meaning of existence today. Proof of this can be found by reading the newspapers, listening to radio programmes and revelling in the images presented by television: a single existential perspective (if we can call it that) prevails over everything that is expressed by the mass media. Counting on their frenzied applause, this perspective decrees that life is about one thing only: increasing the production of objects, products and leisure activities to the hilt for the benefit of our material comfort.

Produce and consume, this is our motto, and enjoy ourselves: entertain ourselves with pastimes (appropriately termed “leisure activities”) that the entertainment industry and the media flood the market with in order to fill what can only wrongly be called "spiritual life"; in order, to be more precise, to fill this emptiness, this lack of concern and action that the word leisure expresses so well.

This is what man’s life and meaning is reduced to today. The life of that "physiological man" who appears to find his greatest fulfilment in satisfying the needs derived from his maintenance and sustenance. It must, of course, be acknowledged that in this endeavour,particularly where the improvement of health and the increase in life expectancy (which has almost doubled in the course of a century) is concerned, the successes achieved are absolutely spectacular. As is the great progress that science has made in understanding the laws that govern the physical phenomena that form the universe in general and the earth in particular. Far from denying this progress, we the undersigned welcome and rejoice in them.

It is this same rejoicing that moves us to express our astonishment and disquiet when faced with the paradox that, just when such achievements have made it possible to significantly alleviate the suffering of illness, mitigate the hardness of work and increase the opportunity to acquire knowledge (to an extent unheard of before and in conditions of equality until now unknown), at a time exemplified by such salutary benefits, all perspectives are reduced to the mere increase of well being and spiritual life runs the risk of being annihilated.

What is at stake is not, with the exception of an ecological disaster, the material benefits thus achieved but spiritual life. Proof of this can be seen in, among thousands of other things, the simple fact that it has even become problematic to use the term "spirit". Such is the materialism that impregnates the most intimate confines of our thoughts and heartsyou only have to use the term "spirit" positively, or attack the prevailing materialism in its name for it be automatically considered loaded with pejorative religious, if not esoteric, connotations.

For this reason, it must be made clear that it is not religious concern that motivates us, independently of the fact that we may consider the relationship between "the spiritual" and "the divine" to be close.

The disquiet that motivates us is not caused by the death of God, but the death of the spirit: the disappearance of this source of strength that made man all that he is and not simply an organic entity. Our disquiet stems from the apparent disappearance of this life force thanks to which man “is” and does not merely “survive” in this world. This longing to express all their happiness and distress, all their jubilation and their unease, all their assertion and enquiry into wonder which no reason will ever be able to explain: the wonder of being, the miracle that men and things are, that they exist, that they have meaning and significance.

Why do we live and die? We, who think we have mastered the world, the material world? Why are we here? What is our purpose? What are our symbols? Which are the values without which no man or community would exist? What is our destiny? Although this is the question that forms the basis of and gives meaning to any civilisation, ours typically ignores and pours scorn on this kind of question: a question that is not even asked, or if it were, would be answered by saying: "our destiny is to be deprived of destiny, to lack any destiny other than our immediate survival".

To lack destiny, to be deprived of a regulating principle, of a truth that guarantees and guides our steps, such an absence, such nothingness, is surely what the maelstrom of products and distractions with which we cram ourselves full and blind ourselves, is intended to fill. This is the root of our ills. Yet it is, or rather could be if we saw it differently, the source of all our strength and greatness. The greatness of free men; men who are not bound to any absolute Principle, any predetermined Truth; the honour and greatness of men who seek, enquire and strive with no direction or fixed destiny. Free, that is to say, vulnerable, with neither shelter nor protection. Open to death.

Outlining the above perspective does not mean or resolve anything. Unlike most manifestoes, this one does not set out to propose measures and actions or solutions. Fortunately, the time is long gone when a group of intellectuals might imagine that by giving expression to their concerns and plans on a sheet of paper as blank as the world they wished to form, it would follow the set path. Such is the illusion - the lure - of revolutionary thought which, having managed to put the forceps of power to the service of their ideas, did in fact succeed (but with the consequences we are aware of) in transforming the world for a few brief, horrendous decades.

The world is certainly not the blank page that the revolutionaries imagined it to be. The world is a fascinating and sometimes terrifying book in which the past, enigmas and breadth are interwoven. We the undersigned do not seek to give expression to any new programme for redemption on any new blank page. Above all, we aim, although it would be asking a lot, to bring together voices united by an apparent unease.

It would be asking a lot, in fact, as the strangest, not to say the most troubling, thing is that this apparent unease has not so far found any real channel for expression. Even more worrying than the very death of the spirit is the fact that, with the exception of a few isolated voices, our contemporaries seem to be completely indifferent to it.

For this reason, the main objective of this manifesto is to ascertain the extent to which these reflections are likely to produce a slight, perceptible or (perhaps) loud echo. In spite of the overwhelming pessimism of this manifesto, it does cling to the crazy hope that it is impossible that only a few isolated voices are occasionally raised to oppose a view that is typical of our time. Inasmuch as this view continues to prevail, it is evident that concerns such as those expressed here will only take the form of a cry or a denunciation. That is clear. However, it is not clear that this cry should not even form part of that critical, challenging and transgressing mood that so typified modernity, at least at the outset. As if everything was the best it can be in the best of all possible worlds, almost nothing remains of that critical attitude. The only thing today that moves people to protest are ecological demands (as legitimate as they are for the most part inseparable from base materialism), to which we could add the remains of an equally materialist and outdated communism that does not even appear to have heard of the crimes committed under its flag which are only comparable to those carried out by the other apparently opposite totalitarianism.

Since the anxious and critical attitude that formerly honoured modernity has disappeared and our time has been given over exclusively to the lords of wealth and money, whose spirit impregnates its vassals equally, the only option left is to send up a cry to express our anguish. That is the purpose of this manifesto. In addition to sending up a cry, it also seeks to ignite a profound debate. This is not to say that the questions explicitly set out here, or the many others that these imply, cannot be fully expressed in the short space of a manifesto. For this reason, the purposes of the manifesto would be abundantly served if its publication were to spark off a debate in which all those who are troubled by the concerns set out here were to participate.

We shall set out only a few of the questions that might give rise to this debate. If “the issue of our time”, to paraphrase Ortega, is none other than this profound paradox; the need for destiny to reveal itself to those who are deprived of it and who have to remain deprived of it; if our question is the demand for meaning to be revealed to a world that discovers, even covertly anddistortedly, all the meaninglessness of the world; if this is, in fact, the “issue”, the question then is: through what channels, by what means, with what content, with what symbols and from what plans can such a meaning begin to reveal itself?

The above paradox, to have or not have destiny; to assert meaning established on the very meaningless of the world; all this perilous but ennobling exercise of balancing on the edge of the abyss, all this staying on the uncertain border that mediates between solid ground and emptiness. Does it not all look like the abyss, the very paradox of art: real art that has nothing to do with entertainment and is sold under the same name today? "We have art in order not to perish because of the truth", that is to say, rationality, Nietzsche said. Perhaps, perhaps art could bring the world out of its apathy and torpor. Certainly, for this to occur, artistic imagination would have to find renewed momentum and vigour but that would not suffice. No longer being considered so much entertainment, like a mere aesthetic ornament, art would have to recoup its rightful place in the world. It would have to become understood as the expression of truth that art is and that has nothing to do with mere contemplation by an idle spectator.

But is this possible in a world in which not only banality and mediocrity but also ugliness (architectural and decorative ugliness, ugly clothing and music, etc.) seem to be becoming one of its focal points? Is this live presence of art possible in a world dominated by the sensitivity and applause of the masses? Is it possible for art to become central to the world without reviving (but how?) what it was for centuries, authentic very much alive popular culture? This culture has disappeared today, burned on the altar of equality whereby everyone is measured by the same yardstick and is forced to submit to a single culture that our society considers not only feasible but legitimate. Is it not then the question of equality itself – its conditions, possibilities and consequences - that remains unanswered and inevitably has to be tackled?

Let us consider one last question, perhaps the most decisive. The decline of spirit, deplored here is closely related to what could be called disenchantment with a world that has brought about the deepest of disenchantments. It has annihilated the supernatural powers that, since the beginning of time, governed men’s lives and gave things meaning. We do not need to insist on the need for this disenchantment to explain the physical phenomena that form the universe. The weapons of reason whose material conquests (both theoretical and practical) are well proven are essential for it.But are these not the same weapons and the same conquests that corrupt everything when, no longer applied to the material realm, they try to explain the spiritual one? Is it not the power of reason that reduces everything to the mechanics of cause and effect, function and utility, when it tackles the meaning of the world, when it tries to deal with the meaning of existence? Does the basis of the problem not lie in this excessive power that man attributed to himself by proclaiming himself not only "lord and master of nature" but also lord and master of meaning? It is true that it is only through the presence of man that this, the most wonderful “thing” of all, which we call meaning, arises. But on no account does this imply that meaning is at man’s disposal, that he is its lord and master or that he dominates and controls a mystery that will always transcend him.

When it comes down to it, this transcendence is none other than what for centuries was called "God". Is seeing things from such a perspective not then equivalent to posing the question (but on radically new bases) that modernity had thought it could obviate for ever: the question of God?

As with the others, let us leave this last question open, the question of an unusual god (perhaps it should be written in lower case), the question of a god who, lacking his own reality (not belonging to either the natural or the supernatural world) would be as dependent on men and imagination as they are on him and it. What world or order of reality could such a god belong to? He certainly could not belong to the supernatural order whose physical reality has been negated by His Holiness the Pope, who (although nobody was aware of it) in July 1999 stated that "heaven […] is neither an abstraction nor a physical place among the clouds but a relationship with God that is alive and personal". Where does god dwell? What does divine nature consist of if no physical place is suitable, if it is only a matter of a "relationship"? Where does god dwell if not in this even more prodigious and marvellous place that is composed of the creations of the imagination?

In the end, the question of god is none other than the question of the imagination, enquiry into its nature: that force which creates signs, meanings, beliefs and passions, institutions and symbols out of nothing; that force on which perhaps everything depends and over which, as is to be expected, modern man also claims to be lord and master. That is how this man sees it who, looking at yesterday or today’s signs and symbols with a condescending smile, exclaims mockingly, “Oh, it’s only imagination!”, lies then.